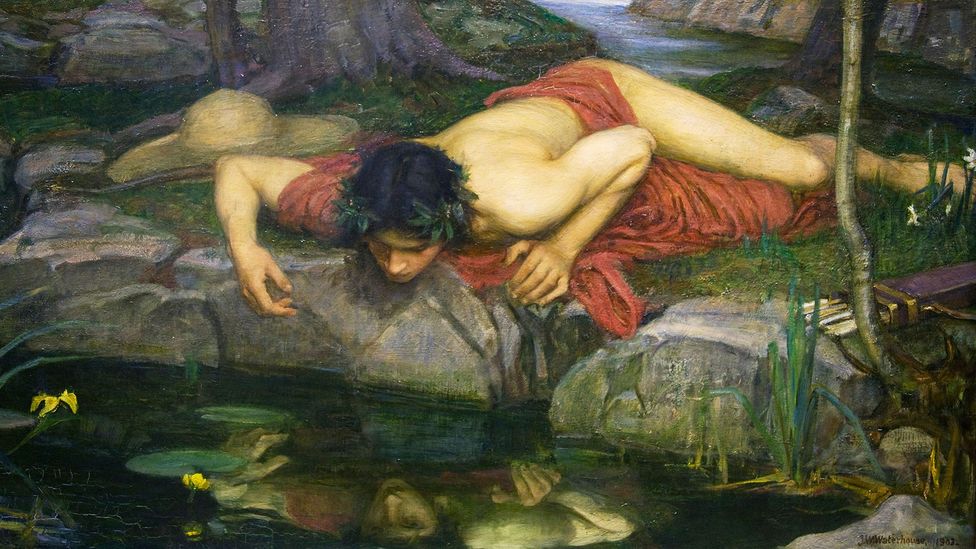

“You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur.”

— Margaret Atwood

History wasn’t changed through physical beauty. Imagine the world we’d live in if Joan of Arc, Marie Curie, Florence Nightingale, Margaret Hamilton, and Rosa Parks spent their days preoccupied with beauty ideals of their day and their patriarchal-chosen roles, instead of on their passion, their skills, their minds, and societal change. Intuitively we know character and intelligence is what matters, yet subconsciously, women still internalize patriarchal standards that value self-objectification to the gain of the cosmetic, plastic surgery, and social media conglomerate. Negative body image is linked to depression in adulthood, and with depression and anxiety doubling in youth, it’s more important than ever to dismantle faulty ideas that cause unnecessary burdens to today’s youth. Self-objectification literally impairs cognitive performance. Beauty isn’t worth, worth is inherent. Here’s how to stop worrying about being conventionally consumable.

Empirical evidence has shown that self-objectification erodes cognitive performance and endangers health. We as a culture should be paying more attention to dismantling the obsession with beauty instead of expanding it. Research contends that body dissatisfaction is a major concern for both men and women, and the pursuit of attractiveness is a big risk factor for the development of eating disorders and muscle dysmorphia.

What Is Self-Objectification?

Self-objectification occurs when people treat themselves as objects to be viewed and regarded based upon appearance (Fredrickson and Roberts, 1997; McKinley, 2011). “Literature has largely elucidated links between self-objectification and damaging outcomes in both men and women.” It occurs in women when they absorb societal standards placed on their looks. The objectification theory (Fredrickson and Roberts, 1997) contends that women are looked at as objects by society with a focus being placed on their bodies instead of their abilities. The pervasiveness of these objectifying experiences socializes women to internalize the male gaze, an evaluative third-person perspective on their bodies—objectification theory (McKinley and Hyde, 1996; Fredrickson and Roberts, 1997).

“Experimental research has shown that heightened self-objectification promotes general shame, appearance anxiety, drive for thinness, hinders task performances and increases negative mood (Moradi and Huang, 2008; Gervais et al., 2011; Rollero, 2013; Tiggemann, 2013). Consistently, correlational studies have found that self-objectification is related to appearance anxiety, body shame, positive attitudes toward cosmetic surgery, depression, sexual dysfunction and various forms of disordered eating (e.g., Miner-Rubino et al., 2002; Calogero, 2009; Calogero et al., 2010; Peat and Muehlenkamp, 2011; Tiggemann and Williams, 2012). Most correlational studies have been cross sectional, but some longitudinal data are available as well and report similar outcomes (McKinley, 2006).”

Fredrickson and Roberts (1997) define sexual objectification as, “occur[ing] whenever a woman’s body, body parts, or sexual functions are separated out from her person, reduced to the status of mere instruments, or regarded as if they were capable of representing her” (p. 175). Theorists suggest that girls and women are exposed to sexual objectification in three primary ways: (1) direct interpersonal experiences of objectification (e.g., unsolicited appearance commentary), (2) vicarious experiences of other women’s objectification (e.g., overhearing men’s appearance commentary about other women), and (3) objectified media representations of women (e.g., images in which women’s bodies are fragmented) (Fredrickson and Roberts, 1997). All three forms of objectification are now commonly experienced by women on social networking sites such as Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter that have been developed since Fredrickson and Roberts’ early work (see, for example, Bell et al., 2018; Ramsey and Horan, 2018; Butkowski et al., 2019) in addition to traditional media and face-to-face interactions.

While studies have shown that men report lower levels of self-objectification, young adult males are growing progressively more preoccupied about their physical appearance (Weltzin et al., 2005; Moradi and Huang, 2008). Men’s self-objectification is correlated with lower self-esteem, negative mood, worse perceived health and disordered eating (Calogero, 2009; Rollero, 2013; Register et al., 2015; Rollero and De Piccoli, 2015). Further, self-objectification can explain drive for muscularity, excessive exercise and steroid use in men (Daniel and Bridges, 2010; Parent and Moradi, 2011).

Furthermore, self-objectification is theorized to impair cognitive performance through the consumption of attentional resources (Fredrickson and Roberts, 1997). Behaviors can include mirror-checking, frequent selfies, constant self-criticism in reflection and photos, and comparison to images in the media and other women.

Those lucky enough to have been raised to value knowledge and character, those that didn’t fall to the strangle-hold of media beauty standards, can still later in life develop this ‘voyeur’ Atwood described, that performs beauty ideals for external validation. Never truly at peace with oneself, never existing for oneself, always hyper self-aware of one’s external presentation.

The Truth

Beauty isn’t worth, worth is inherent. Stop worrying about being conventionally consumable. Stop being your own voyeur. Existence is an act not a state. The movers of history didn’t immortalize their name with beauty but through their depth of character and mind. Reject self-objectification, remember that you have inherent worth.

We can not keep upholding physically and mentally harmful patriarchal standards that once socialized women to believe they should be seen not heard by prioritizing looks. We must shed the male gaze, shed the need for external validation, and the obsession with beauty.

Once you detach yourself from external validation, you’re unstoppable. Your only competition is your past self, you do things out of passion and joy. You’re free to exist as authentically and positively as you want.

Biblical Approach

The obsession with physical beauty is yet another carnal, vain pursuit that fades. We must see each other and act as the Lord sees us.

1 Samuel 16:7: But the Lord said unto Samuel, Look not on his countenance, or on the height of his stature; because I have refused him: for the Lord seeth not as man seeth; for man looketh on the outward appearance, but the Lord looketh on the heart.

In sum, a great number of studies grounded in objectification theory have elucidated links between self-objectification processes and relevant psychological outcomes both in female and in male populations. Self-objectification is theorized to increase negative affect and to impair cognitive performance, primarily through the consumption of attentional resources (Fredrickson and Roberts, 1997). An increasing body of empirical evidence supports the idea that self-objectification results in decrements in cognitive performance, which we define here as critical reasoning and/or logical reasoning ability, in a variety of contexts.

Leave a Reply