Industrial capitalism has relied on cost minimization through cheap labor since the Gilded Age — it’s now moved overseas where it’s had unsafe, exploitative ramifications in developing nations. The decline in US manufacturing since the 1970s has without a doubt transformed the economic landscape to the detriment of non-college educated American workers. The 14.3 million outsourced jobs are more than double the 5.9 million unemployed Americans. Globalization of outsourcing practices has had unsafe and exploitative ramifications in developing countries. As sweatshop labor overseas produces our most essentials commodities, can there truly be “no ethical consumption under capitalism?“

Is there a better economic solution to help both American companies, and developing countries industrialize?

The flight of manufacturing jobs out of the U.S. has drastically impacted the economy for the worse. People without access to the “college wage premium” have seen their earnings decline in this technology and service industry age with less manufacturing jobs. Deindustrialization has decreased these well-paying jobs for many Americans and only low-wage jobs have been growing for those who are non-college educated. The stagnated minimum wage has exacerbated this income inequality as the rich continue to reap a higher share of profits produced by the workers.

In fact, the minimum wage peaked in 1968 at $11.18 when the cost of a four-year public university was $329.00, per the National Center for Education Statistics, a manufacturing job bought you a house for $26,600.00, and the cost of living was 657% lower.

Source: Economic Policy Institute 2015

The vertical axis shows the percent change in productivity and hourly wage relative to 1947. After almost two decades of growth of productivity and wages, wages have stagnated since the 1970s, reflecting the restructuring of American firms. This is all despite the fact that the average worker was far more productive in 2014 than the same worker would have been in 1970.

How does this contribute to income inequality? It means that workers, on average, receive a smaller share of their average economic output than four decades ago.

In the manufacturing age, a working-class family in Detroit in the 1940s had a much brighter set of economic opportunities than a child growing up in today’s Detroit. But beginning in the 1970s, employment in manufacturing began a steep decline due to both technological advances and outsourcing to countries with much lower wages such as China. Another key trend has been the shift towards service sector jobs. With disappearing factory jobs, millions of factory workers that spent their lifetime acquiring knowledge and skills to be a skilled factory worker lost employment and found themselves in a new job market. Places like Detroit, Michigan — once the home of the auto industry — have now become emblems of the impact of the changing economic system.

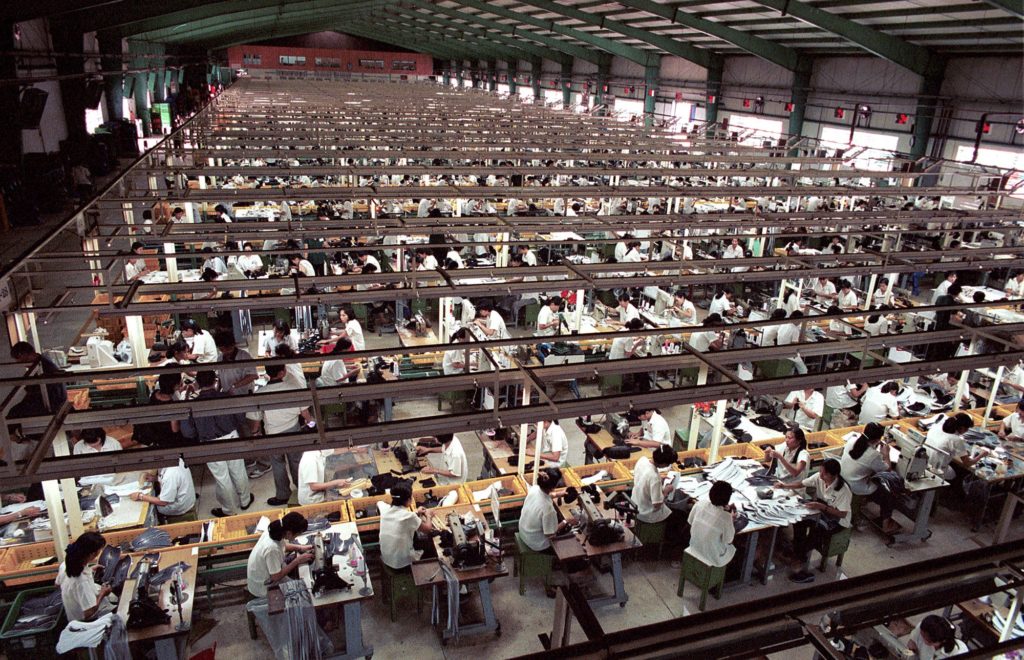

Increasing globalization — the growing permeability of national borders and increase in flows of goods and services — has resulted in cheaper imported goods from these countries, the relocation of manufacturing jobs and rise of exploitative and unsafe sweatshops. Globalization has led to outsourcing — where products are designed, built, and marketed through global supply chains where cheap labor is available. Almost every product in our home is made overseas in sweatshops — from quintessential American companies like Apple to the clothes on our back. In 2015 all 230 million iPhones and 53 million iPads Apple sold were manufactured overseas by Foxconn in factories in Shenzhen, China. Apple workers are exploited through long hours for indentured servitude wages so we can have the latest 0.1 mm bigger screen.

The U.S. trade deficit with China in 2019 was $345.6 billion (18% less than 2018’s $419.5 billion deficit.) U.S. exports to China were only $106.6 billion while imports from China were $452.2 billion.The biggest categories of U.S. imports from China were computers, cell phones, apparel, and toys and sporting goods

An explosion in Apple’s overseas Foxconn plants in Chengdu, China killed two workers and hurt a dozen. While in Wintek, hundreds were injured after being forced to use toxic chemicals to clean the iPhone screens we type on.

Can the decline in US manufacturing be reversed through tax cuts or trade policy? Since World War II, the share of private employment in goods production (including manufacturing) has steadily declined from just short of 50 percent to just fewer than 20 percent.

Is ethical consumption possible in our globalized world economy though? Of course, in our current geopolitical environment every ethical condition — environmental, fair treatment of migrant workers, and more can’t be satisfied by simply moving manufacturing to the U.S. Furthermore, all current work on average varies in degrees of exploitation, workers receive a smaller share of their average economic output than four decades ago.

The Good Place depicted this dilemma of making perfect ethical choices in an imperfect world– are we contributing to unethical practices if we buy a tomato imported from exploited Mexican farmworkers whose starvation wages are withheld until the end of their three-month contract? How about the produce aisle produced from the labor of exploited migrant workers making $5 an hour who do backbreaking work to feed America? Though efforts like “Fair Trade” labels have been made, making wholly ethical choices is impossible without uprooting the global system of worker exploitation and inequality.

But what are the effects of ending sweatshop labor overseas? Can these 14.3 million jobs ‘return?’ Not to the detriment of American companies’ profit. Even Donald Trump’s NAFTA renegotiation tariffs on Mexican and Chinese imports and trade war failed to bring back jobs. Imposing laws to artificially restrict outsourcing just makes these companies less ‘competitive’ since they’re actually forced to pay legal wages to American workers. The entire American capitalist model has relied on minimizing costs through exploitative labor since the Gilded Age — it’s now just moved overseas.

While developing nations benefit from outsourced jobs, the exploited workers do not fairly reap the earnings of their labor. A case study (Akinyemi, 2016) on the impacts of outsourcing to developing economies found that outsourcing has indeed helped reduce unemployment in countries like India and increased their GDP. However, macroeconomic benefits are gilded — they don’t show the scale of exploitation of the 250 million children ages 5 to 14 worldwide forced to work in sweatshops in developing countries and the $0.13 average Bangladesh worker’s wage, $0.26 average Vietnamese worker’s wage, and $2.38 (highest apparel wage) Costa rRican rworker’s wage.It takes an apparel worker in a sweatshop an average of working 70 hours per week to exceed the average income for their country.

We are not doing these developing economies a ‘favor’ by outsourcing — we are not helping these 250 million children working for cents an hour obtain an education; we are contributing to an exploitative capitalist system that refuses to pay fair wages to workers in the U.S. in the pursuit of maximum profit. A pure ethical consumer choice can’t be made in this global economic landscape of unintended environmental, farm worker, and sweatshop labor exploitation consequences. But we can stop pretending the exploitative labor behind our technology, clothes, and household appliances are a viable and ethical economic model. American jobs can’t be forced home, but the underlying system of exploitative labor where workers reap mere crumbs of their labor must be uprooted – policy by policy.

Leave a Reply